| Roland Seim

Censorship Shall Not

Take Place - Even in Popular Culture?

An Introduction to the Current Situation

in Germany.

Dear colleagues, dear audience,

first of all I would like to thank the Goethe-Institut and Dr

Norbert Spitz very much for the friendly invitation to the wonderful

city of Beirut. I am very honored to give this key note lecture

for our symposium.

I apologize not to make a free speech on free speech. But it's

better to read good than to speak bad English.

Abstract: My paper

deals with the issue of free speech versus censorship. It shows

us some cases of interdicted media objects and explains the conflicts

of free expression. Furthermore it examines both the impact of

censorship and the fascination of banned objects. The censors

and fans of such material are bonded together in a kind of a symbiotic

relationship. The paper shows that restrictions are accepted by

the majority but proves both intolerable and fascinating for the

fans of the bizarre. While banning explicit material may be ineffective,

it clearly delineates socio-cultural boundaries and renders standards

of our media use explicit in this controversial debate.

"If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to

tell people what they do not want to hear", George Orwell

wrotes in Animal Farm.

Every society has its own sensitivities, taboos,

boundaries, and degrees of freedom. So, the difficult topic "freedom

of media, art and expression versus censorship" is not only

a problem of dictatorships or fundamentalistic regimes. This text

wants to explore, that even Western democracies try to gain influence

against unwanted contents, although it is not so politically violent

as in other regions.

Some of the main questions are: Is there censorship in Germany,

and if, how does it work? Does it make sense? Which topics are

forbidden? Why is banned material so fascinating?

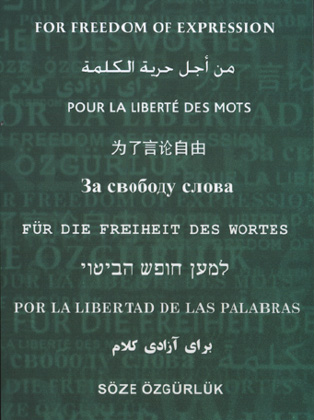

The most constitutions guarantee the right of personal freedom

and free expression of opinion as a result of the Enlightenment,

written down in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948,

the Lebanese politican Charles Malik was a co-author of. (Art.

19: "Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression...").

In Germany Art. 5 of our "Basic Law" (1949) promises:

Art is free, and, a censorship shall not take place.

But, how tolerant can we be when faced with intolerance? What

about hate speech, pornography, media violence, right-wing extremist

or terrorist propaganda, blasphemy, xenophobic slander, libels

and so on, even when they occur in literature or in a work of

art in a wider sense? This is a complicated issue. German constitution

tries to resolve this dilemma by installing some restraints: "These

rights are limited only by the regulations of general law, legal

regulations on the protection of juveniles and the rights of personal

honor." Many sections of the German criminal code forbid

the named offences. Every state and government, even if open-minded

and liberal, restrict offensive contents more or less by law.

The problem is, how to draw juridically the line between art and

crime. Are jurists and judges really able to define what art is

and what should be allowed in culture?

A censor, the dictionary informs us, is an official who examines

books, movies, etc., for the purpose of suppressing parts deemed

objectionable on moral, political, military, religious, or other

grounds. Technically speaking there are external and internal

kinds and three methods of censorship, I call it "weapons

of mass media destruction":

1. Pre-censorship: Prior restraint and preclearance; deleting

or softening material before broadcasting or publishing. This

occurs in the several self-regulation boards of the movies, PC-games,

television and so on.

2. Self-censorship: the internalization of the "scissors

in your head" to avoid trouble is difficult to prove, because

we have no comparison between the original and the reducted version.

Mostly a type of economic censorship.

3. Post-censorship: after publication, objectionable material

can be put on the index by the Bundesprüfstelle (Office for

the Control of Publications Harmful to Youth), or can be totally

banned by court including seizure and confiscation. Restrictions,

however, are in force for the more than 80 million citizens of

Germany. Any individual can institute legal proceedings against

dubious media products at any youth welfare department. All bans

are mentioned in the lists of the official organ "BPjM Aktuell".

The Censors and Their Objects

Censorship can be understood as a kind of cultural regulation.

As with any other reasonable measure, censorship must try to balance

the claims of the common good against the claims of individual

freedom. In general, censorship as a mandatory requirement depends

on the commonsensical application of contemporary community standards,

mentality, and conventions; in particular, it is implemented according

to the taste and character of individual readers and viewers.

But even the censors act on their own subjective tastes to prevent

feared anti-social attitudes and actions when they assess the

intention and the possible effects of cultural objects they examine.

Even a few objectionable sequences or pages that epitomize, so

to speak, the bad-taken out of context-could be sufficient to

ban an entire film or book. But there are at least two sides to

everything. One person's obscenity is another person's bedtime

reading. Art or morbid filth? Finally, it's a question of practical

ethics and aesthetics as to whether one accepts and permits or

condemns and banishes crass descriptions of the physical aspect

of the body for example.

Most intrusive censorship is supported as taking place in the

interests of protecting young people. These censors are likely

convinced that they are performing a positive service to society.

They have to believe that no social system-even a pluralistic

democracy-can allow their members total and absolute freedom of

informational interchange or they could not do their work.

Insofar as the criteria censors use to distinguish between prohibition

and permissible tolerance are in flux, censoring authorities must

rely on all sorts of tacit assumptions of propriety in assessing

how to do their work. Even today in the liberated time of a postmodern

"anything goes" climate, the government feels the necessity

to put the 'kabosh' on the free flow of certain kinds of information.

Decision makers must cope with the problem of determining what

would be harmful to minors or might endanger social stability.

Many laws prohibiting modes of expression in literature, films

and other media thought to be depraved or corrupt are currently

deemed valid, but the application of these laws may be questionable.

Even if there does not exist a major official or state-supervised

agency concerned with pre-censorship in Germany as the Securité

Générale (at least until 2005) in Lebanon, many

authorities closely scrutinize the limits of liberty. Only the

FSK (Freiwillige Selbstkontrolle der Filmwirtschaft), the German

voluntary self-regulating Board of Film Classification, performs

a pre-censorship assessment because all movies are required to

be submitted before their first showing.

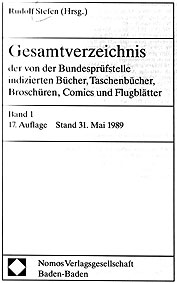

Above all, the courts and the so called "Bundesprüfstelle

für jugendgefährdende Medien - BPjM" (a unique

federal Office for the Control of Publications Harmful to Youth)

can take action against disapproved items by putting them on its

index to prevent minors from coming into contact with possibly

harmful material. They remain at least for 25 years on it, before

cancelled ex officio. Special committees with from 3 to 12 mostly

honorary members of socially-relevant interest groups, such as

churches, youth welfare organizations, teachers, publishers and

distributors decide if an item should be placed on the index.

As we shall see, it's a two-headed monster because some fans of

censorable material use the index as a kind of shopping list.

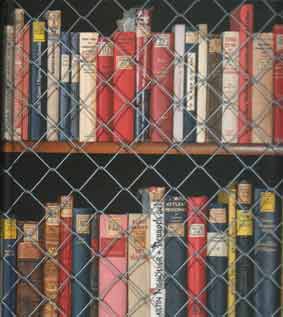

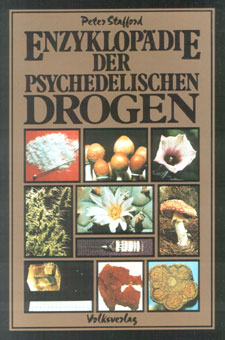

What nearly nobody knows: About 15,000 videos, books, comics,

records, computer games, Internet contents, and so on are restricted

by virtue of being on this black list. These items therefore are

forbidden to minors because some censors deemed that viewing such

material would result in "social-ethic disorientation"

or wrong moral concepts due to explicit obscenity, sex, drugs,

violence, occultism, encouragement of suicide, or political extremism.

Indexed things may not be advertised or sent via the mail. Most

media content that is banned, comes from foreign countries, in

the area of literature for example were put on the index: Bret

Easton Ellis' American Psycho, William S. Burroughs' Naked Lunch,

Dan Kavanagh's (Julian Barnes) Duffy, and Timothy Leary's Politics

of Ecstasy. All these bans pose challenges for fans of interdicted

items.

Additionally about 600 books, films, records etc. are totally

banned in Germany even for adults according to a court decision.

Even if Article 5 of the German Constitution establishes freedom

of speech, many criminal and civil laws limit the possibilities

of free expression. The reasons for prohibition are varied, such

as: Hard core pornography under § 184 Criminal Code (about

200 objects banned), glorification of violence under § 131

(about 300 objects banned), libel or hate speech under §

130 (about 120 objects banned, especially Nazi propaganda and

the so called "Auschwitz lie"). Any judge can make his

own decision as what is to be banned nationwide for "antisocial

harmfulness" (in German: "sozialschädlich").

But every isolated case is a matter for interpretation and many

questionable decisions are inevitably made. The most recent case

of a book ban by the Federal Constitutional Court refers to Maxim

Billers novel "Esra". It gets forbidden because of violating

the personal rights of the turkish protagonist, the author's ex-girl

friend, because of describing intimate details of their relationship.

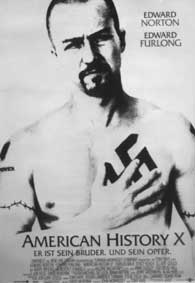

The main ground for book and record banning in Germany is Nazi

propaganda, and I think this exception to the right to freedom

of speech might be reasonable: More than hundred publications

and records are forbidden for xenophobic incitement, hate speech,

right-wing extremism, race hatred, vengeance theories of a Jewish

conspiracy, or because they question the Holocaust or German war

guilt. Showing the swastika is proscribed in popular cultural

circumstances, except in clearly anti-fascistic purposes.

But even manuals for self-defense, like many books from the US

publishers Paladin Press and Loompanics, have been seized by Canadian

and German authorities, for example "Homemade Explosives",

although it is "sold for informational purposes only".

In the USA those books were unrestricted available because of

the First Amendment; in Germany, they have been banned since 1991

because they contain instructions on how to commit criminal offenses.

But I guess, after 9/11 especially the USA are more restrictive

concerning titles as "Terrorist's Handbook" or "Anarchist's

Cookbook". Security wins over free speech.

But it is questionable to condemn virtual reality artworks or

the artificial fantasy world of the movies, literature and comics.

Concerning motion pictures, the violation of human dignity by

the depiction of graphic violence is the main reason for prohibition.

Let me show you some examples of films that are prohibited in

Germany: The Evil Dead by Sam Raimi has been banned in Germany

since 1984. The censors passed this film only in an edited R-rated

form), Halloween Part 2 (produced by John Carpenter), Phantasm

(Don Coscarelli) and Braindead (Peter Jackson).

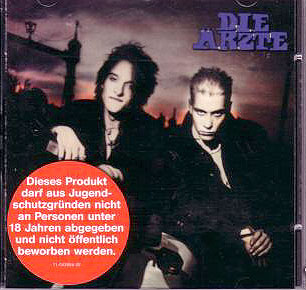

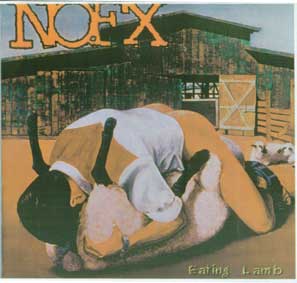

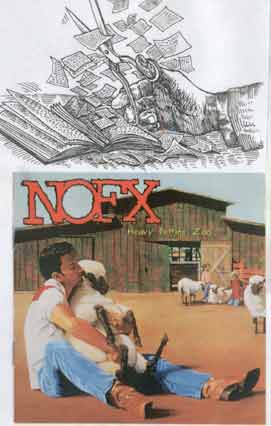

Music is no less subject to censorship than any other form of

artistic expression. In the Eighties a lot of heavy metal records

and covers were put on the index for violence. Some confiscated

records are: Butchered at Birth (by the death metal band Cannibal

Corpse) because of violent cover artwork, and Eating Lamb (by

the US-Punk-Band NOFX, 1996) because of the depiction of sexual

intercourse with an animal. The band issued two different versions

of cover art. The LP version Eating Lamb was banned in Germany

in 1996 because of "bestiality" ("sodomistic porn"),

however the similar illustrated CD Heavy Petting Zoo was not.

Currently, the explicit lyrics of rap music are under discussion

because they advocate violence against women, show no dignity

for people, and play down drug abuse. Dozens of titles are on

the index. But silencing, even of music, is a world-wide problem.

A special case is the Internet, which is not as free as you might

think. All websites, that are put on the German index (about 1,500,

but this list is confidential and will not published since 2003),

were filtered out and can not be found via search engines like

google.de. Governments argue, that the Cyberspace shall not become

a kind of lawless parallel-universe, so, monitoring and blocking

takes place if needed. To catch terrorists, authority wants to

implement a so called "federal trojan horse" on private

computers for official online searches.

The Current Situation of Ambiguity

"Censorship happens whenever some people succeed in imposing

their political or moral values on others by suppressing words,

images, or ideas that they find offensive" says Marjorie

Heins (p. 3). Censorship always has a Janus-face. It creates an

odd scenario of ambiguity. On the one side, the government and

many pressure groups try to suppress unacceptable media content

within the bounds of human rights and constitutional law regarding

freedom of speech, art and press. On the other side, forbidden

things become rather attractive to many fans because of the specific

thrill of interdiction. Michel Foucault once said that a ban makes

a book valuable. This two-faced phenomenon of repressive control

versus self-determination of mature users raises questions about

how fans on the one side put into practice their fascination with

breaking the taboo and, on the other side, why and how censors

ban the items they select.

Let me go back to some basics reflections:

We are socialized by the different kinds of mass media that shape

our view of life and influence our behavior. Socio-cultural experiences

and associations do condition our opinions and preferences. Moreover,

the contents of media are to some extent a kind of refractive

mirror of society. How tolerant or restrictive we treat media

reveals to us a significant part of our current socio-political

situation and moral beliefs. But neither the official picture

of the mainstream culture nor the research that often criticizes

the portrayals of sex and violence in the media to justify control

and censorship reveal the behavior of people who are fascinated

by banned (and often strange) contents.

But even these materials are part of the cultural landscape, although

they get rarely into the focus of academic interest, despite the

fact that a huge number of theoretical studies have been written

especially by jurists and social scientists. What is the quarrel

between censorship and free speech all about? How are these deviant

products of the media used by which kind of consumers in their

everyday lives, and why are these items "media-worthy"

for them? And, what point of view do the censors have? What is

at stake in banning dubious contents, and what is at stake in

allowing the free flow of uncensored media?

The Fascination of the Banned

The consumer has more rights to purchase what he or she wants

than the producer has rights to spread his ideas, because the

laws (and the risks) have always been aimed primarily at directors,

authors, publishers or editors. In other words, the law does not

forbid consumers from reading banned books or watching banned

films (except child porn, possession of which alone is criminal)

if you find or own one. However, sale and trade is prohibited

so these items could be confiscated and the producers or distributors

punished.

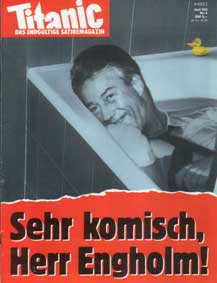

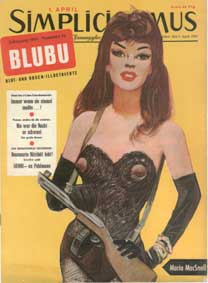

Violent media contents and latent sexualization seem to be quite

common now. In the Fifties this issue of "Simplicissmus"

- a German satire magazine - was punished for obscenity. Early

sex educational books as "Helga and Bernd" had to show

their item in a self-censored way. Today people are exposed to

a constant stream of more or less questionable items. Cable networks,

videotapes, computer games, and the Internet offer the possibility

of getting anything you want. Anonymity ("Pretty good Privacy")

and encryption technology ("FreeNet" or "TOR")

could neutralize the ability to wiretap and to censor. In this

confusing area, an index is unintentionally, of course, a point

of departure helping some fascinated individuals to select what

are probably the most exciting offers. Reading an index is like

looking into an area that moralists see as the blackest depths

of the human soul and the farthest reaches of society's underground.

Already the disreputable circumstances and the feeling of doing

something forbidden thrill and entice the fan. The motivation

for getting curbed stuff may vary, but like a "Pavlovian

Reflex" every authoritarian restriction on the publication

and distribution of suspicious material inflames the desire among

fans of the banned to know what one shouldn't know.

The mainstream with its social definitions of good taste, impose

taboos and speech codes that become predictable and boring to

the connoisseurs of the really thrilling stuff. They crave unfiltered,

unfettered gore, so they set out searching for the suppressed.

Banned films, books, comics, records and so on strongly attract

the buffs who want to test the limits and explore the 'dark side'

as a patterned evasion. Most of these fans may come from the middle-class,

and are young and male. Research shows, that juvenile peer groups

that come together for horror film watching sessions reflect elaborate

codes of knowledge of film aesthetics and special effects and

sophisticated interchange and involved behavioral style. Taste

and habitus are not class-specific.

The notion of resistance, the fascination with violating taboos

held by many young people is independent from official orders,

rules and regulations concerning matters of taste. If a case of

dubious suppression occurs, the public debate regarding the principles

of free speech and human rights is dramatized for a short time

in the feature pages, although most of those writers have apparently

not seen or read banned material.

Beside the superstructure of the official opinion of political

correctness and judicial bans, which mainly are approved by the

"moral majority", there are many sub-cultural scenes

where groups try to counteract the authorities and their blocking

strategies. In Germany many lovers of deviant, profane media feel

that the state is making up their minds for them. Barred objects

become rather fascinating to many collectors of the weird, who

want to know what the State suppresses. For those inquisitive

persons every ban is a cue (signal) and every index serves as

a compelling shopping list with the special incentive of the taboo

to savor the forbidden fruit, a special prohibited and therefore

hard-to-get rarity. The hunt for trophies.

In negating the act of banning, alternative ways of procuring

materials, along with several strategies of circumventing the

bans, have emerged, for example re-issues under false names, pirated

editions and bootlegging on the black market, or imports of foreign

versions. More open-minded and liberal countries such as the Netherlands

or Belgium, where nearly no media censorship exists, became very

appealing to fans. I would guess that it's impossible to eradicate

a film if some copies survive, especially as Internet downloads.

Prohibition demands obedience, not understanding. Censorship demonstrates

the power of the rulers, and, from the fans' point of view, deprives

them of their own free will eliciting their resistance.

Conclusion

"Every taboo deals with an awakening to the dilemma of curiosity

about something both attractive and dangerous," Roger Shattuck

wrotes in his book Forbidden Knowledge.

We have found a complex situation among certain interest groups

that some people may identify as an aberration from the normal

use of the media, although the provocative topic of "eros

and thanatos" is as old as culture itself. But the dialectical

process linking ethics, moral reasoning and society are perpetually

in tension over the issues of personal freedom vs. social responsibility.

This essay concludes with a consideration of issues that enter

into the debate on how divided and diverse societies decide what

is permissible to broadcast.

The censors depend in their decision to cover, cut or prohibit

special interest films, books etc. on a majority, who either agree

or is indifferent. The examiners of the diverse governmental offices

feel that they are just doing their jobs in the name of public

mental hygiene. They often exhibit a sense of tedium regarding

matters of taste, decency and hallowed icons. Most censors adopt

a taken-for-granted, unreflective approach and do not recognize

that their work depends on a variable "Zeitgeist", shifting

boundaries of discretion, and changing values. When conventional

tastes change they just find new codewords to obscure their underlying

notions of moral and political decency.

On the other side there are the inquisitive fans who feel compelled

to evade restrictions. In their view censorship is an undemocratic

instrument of control. More importantly, it provides a way for

them to experience some form of otherness. Censorship creates

contra-cultural fandoms of people who are exhilarated by the act

of negating what are actually minor proscriptions.

Of course, some regulating curbs may be necessary, especially

on media contents that might constitute a "clear and present"

danger.

You may ask, what is at stake in banning this filthy material?

Well, who can decide for future generations which kind of media

content is unworthy? One characteristic of censorship is that

it is mundane and tacit so that its sphere of influence can be

inconspicuous extended. The consequence could be that a few judges

routinely decide what all others will be allowed to receive. But

the voices of dissent still need to be heard, particularly those

that are rarely found in the power positions of mainstream media.

Cultural history suggests that formerly banned things often convey

a sense of the everyday thinking and acting of the common people.

That is, what is viewed as degraded, unworthy culture in an era

may be more indicative of mundane lives than high culture and

superior art, which reach only a small elite portion of the population.

I submit that an emancipatory practice might be a better way to

master the problems posed by deviant, disturbing or dangerous

content. In order to enhance the media competence/literacy and

the power of discernment of both the fans and the censors, new

ways of understanding sensitive materials are needed. A reasonable

use of control and regulation (bans for instance in the cases

of child porn or hateful, aggressive Nazi propaganda; restrictions

of violent and explicit material in the name of the protection

of young people) is ok in my view, but most of the other prohibitions

are not emancipatory, and, by the way, won't work. To blame media

for social ills (for example the massacre at Littleton High School)

and to demand restrictions is to take the easy route. Of course,

people's behavior and social interactions with others are not

only regulated through laws. Many social norms and everyday practices

facilitate the social life of mankind. Censorship is not the only

way to instill and regulate norms by official actions, but it

is the most simple and discernible effort to accomplish this.

But since imposed restrictions often have the opposite effect,

it is possible that censorship serves more to convince the public

that aberrance is being restrained and that cultural values are

being preserved than it is to actually prevent access to material.

Tolernce and informal human kinds of social control on the face-to-face

level of everyday life are more sensible constraints on the damaging

use of bizarre items as long as interpersonal processes are effective.

"The threat of censorship is real. Laws can also be counterproductive.

For some, they may only serve as labels to heighten curiosity",

says Otto Larsen (p. 95). If bans were removed, novelty would

wear off and satiation would eventually set in. However, a postmodern

scenario of an over-stimulated population with complete access

to uncensored sex, violent media content, offensive and actionable

symbols and racist speech is not desirable. Mysteries are exciting.

Showing everything to everybody could not only be quite dangerous

for the continued existence of society (as the censors fear),

but it would be rather boring for all the trash seeking "truffle-pigs".

But there is no fear of that.

In my opinion, for the most part censorship is obsolete in a global

society, and a helpless attempt of governments and pressure groups

to deal with overtaxing situations. Finally, even ethical reasoned

censorship is a political matter of power. However, German censorship

can not be compared easily with arabian "arriqaba",

this discussion may have showed. We censor contents, not people.

It's more or less a kind of a sportsman's game, not an existential

threat to live.

Possibly in some respects censorship may be not only bad; it may

help us to keep the discussion about human values, the changing

"Zeitgeist", necessary boundaries and the meaning of

culture at all alive. And by the way: The history shows, that

censoring or banning of art, expression and the media has contrary

effects: it arouses our curiosity and heightens the degree of

fame. It's a contradictory affair: The more censors ban, the more

it becomes interesting.

Thanks for your kindly attention. Shukran.

References:

- Green, Jonathon: The Encyclopedia of Censorship, Facts On File,

New York 1990.

- Heins, Marjorie: Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy. A Guide to America's

Censorship Wars, The New Press, New York 1993.

- Larsen, Otto N.: Voicing Social Concern: The Mass Media - Violence

- Pornography - Censorship - Organization - Social Science - The

Ultramultiversity, University Press of America, Lanham 1994.

- Post, Robert C. (Ed.): Censorship and Silencing. Practices of

Cultural Regulation, The Getty Research Institute for the History

of Art and the Humanities, Los Angeles 1998.

- Robertson QC, Geoffrey: Freedom, the Individual and the Law,

Penguin Books, London 1993, 7th Edition.

- Seim, Roland: Zwischen Medienfreiheit und Zensureingriffen.

Eine medien- und rechtssoziologische Untersuchung zensorischer

Eingriffe in bundesdeutsche Populärkultur, Diss. phil. (thesis),

Univ. of Münster, Telos Verlag, Münster/Germany 1997.

- Shattuck, Roger: Forbidden Knowledge. From Prometheus to Pornography,

St. Martin's Press, New York 1996.

Author's Note:

Born in 1965 in Münster, Germany, Roland Seim studied art

history, sociology and philosophy in Münster and Berlin,

and received 1993 an M.A. degree in art history with a thesis on Alfred

Kubin's depiction of "eros and thanatos". In 1997 he

received his Dr. phil (Ph.D.) in sociology at the University of Münster/Germany

with a doctoral dissertation on censorship in German popular culture.

He is a publisher (www.telos-verlag.de), author and was a part-time lecturer

at the Univ. Münster.

Zur Datenschutzerklärung

To

the author's site

|

1

1

2

2

3

und 4

3

und 4

7

7  8

8  9

9 10

10  11

11 12

12 12a

12a 13

13 14

14 15

15 16

16 17

17 18

18